RA 11959 created the Maharlika Investment Corp. with its initial capital coming from the Land Bank of the Philippines (LBP, P50 billion) and the Development Bank of the Philippines (DBP, P25 billion). Contrary to the impression by the framers of the law that these equity contributions were just a portion of the loanable and investible funds of both state-owned banks, they are actually counted as deductions to capital (emphasis authors).

This fact was obvious to the Banko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) and compliance and risk management professionals in the banking industry even before RA 11959 was signed into law. The negative impact on the capital ratios of the LBP and DBP were clearly discussed in this column of Oct. 23, 2023 (https://tinyurl.com/2bryoqyz).

More than one year later, now comes the IMF calling for the recapitalization of the LBP and DBP. (https://tinyurl.com/22xekz9d). This article shows that IMF statement apparently did not show any computation at the bank level, which lead to an erroneous statement with respect to LandBank.

This point is worth repeating, precisely because it was ignored or not appreciated by those giving advice to the lawmakers crafting RA 11959 — these equity contributions are counted as deductions to capitaland not merely part of their loan or securities portfolio — following Basel 3 and the BSP rules provided in the Manual of Regulations for Banks (MORB).

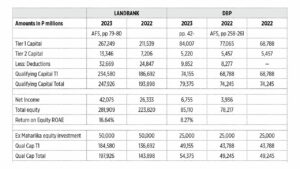

The accompanying chart shows the impact on the LBP and DBP of the Maharlika investment to their Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) and total Capital Adequacy Ratio (total CAR) numbers (Source: LBP & DBP Audited FS 2022, 2023).

LANDBANK CAPITAL RATIOS ABOVE REGULATORY MINIMUMAs the chart shows, the capital ratios of LandBank were still above the regulatory minimum immediately after it remitted its P50 billion equity contribution to Maharlika. Its regulatory minimum capital ratios ex-Maharlika were 10.20% CET1 and 10.73% Total CAR. This is an empirical matter that the IMF staff apparently did not review at the granular level before it issued its statement on the need to recapitalize LandBank so it could exit the regulatory relief.

This is the part that the IMF got wrong in its statement, based on numbers it apparently did not compute (or did not show such computations to support its statement). Put plainly, LandBank did not have to resort to any regulatory relief in meeting the minimum CET1 or total CAR.

LandBank quickly issued a press statement to note that the IMF statement on the need to recapitalize to meet regulatory minimum did not apply to it. That is indeed the case. On the other hand, this writer takes exception to the LandBank press release claiming that its capital ratio is healthy at 16%.

This is the wrong number on two counts:

1. The press release refers to the total CAR ratio, instead of the CET 1 ratio, which is the ratio to meet the regulatory minimum of 10%.

2. The number in the press release refers only to the total CAR (not CET1) before deducting the P50 billion equity investment in Maharlika. It should have shown the ratios after the Maharlika contribution.

As the chart accompanying this piece shows, based on numbers from the LBP audited financial statements, the correct ex-Maharlika numbers for CET 1 are: 10.2% for end-2023 and 12.23% end-2024. It clearly shows that LBP is above the regulatory minimum even after its Maharlika investment. There was absolutely no need for the LBP to be less than forthright or disingenuous and spin it to look better than it actually is. See the last two paragraphs below for the rationale.

SEVERE IMPACT ON DBPDuring the year that it remitted its P25 billion contribution for Maharlika, DBP’s capital ratios went below the regulatory minimum of 10% (CET 1 at 7.4% and total CAR of 8.36%), using the 2022 audited financial statement (FS). These ratios in 2023 improved slightly to a CET 1 of 8.63% and a total CAR of 9.55% but remained below the regulatory minimum.

In remitting its P25 billion equity contribution to Maharlika, the DBP was complying with Section 6.2 of RA 11959, but at the same time it violated Article III Section 12 of the same law, which specifically states that its equity investment should not exceed 25% of its equity.

Similarly, the DBP was in violation of the General Banking Act (RA 8791) Section 24 which limits “equity investments in allied undertakings” to 25% of the bank’s equity. The same limits are contained in the corresponding provisions of the BSP’ MORB.

Complying with the General Banking Act means that with a total equity of P82 billion as of December 2023, the maximum amount that DBP was allowed by law to remit was only P20.5 billion (25% of P82 billion at the time of remittance).

Scenario: if the DBP earns another P6,755 in 2024 and its Risk weighted asset grows to 600,000, its CET 1 ratio would improve to 9.31%.

At this rate, CET1 will hit the minimum regulatory level of 10% by 2025 (assuming no additional regulatory deductions to qualifying capital).

To quantify the impact on the DBP of taking out P25 billion of its equity for Maharlika:

• They fell below the minimum regulatory capital, in violation of BSP’s MORB, the General Banking Act, and even the Maharlika Law (RA 11954) itself. By itself, this necessitated the need to recapitalize DBP, as called for by the IMF.

• The P25 billion in capital which was removed meant taking out P190 billion in lending capacity (on a leverage ratio of 7.5x – as computed in the DBP audited FS).

Instead of shrinking its loan book which it was forced to do, the DBP would have retained the lending capacity of P190 billion and would have earned incremental net interest income of P5.6 billion on a net interest margin (NIM) of 2.95% (actual for 2024), and improved its ROE to double digits. As a reference, the NIM of top unibanks is at least 4%. That is what economists call the “opportunity cost” of taking out money where it could have been deployed, into an entity where it cannot yet be deployed.

This the main reason why my October 2023 piece noted that the ideal scenario would have been a “capital call” scenario where the equity contribution is remitted only when the money is actually needed or when the projects to be funded are identified, and fully vetted.

As a result of the capital shortfall, especially for the DBP, there was news of a request for a regulatory relief from the minimum capital requirement and renewal of prior requests for dividend relief. This would temporarily suspend the declaration of dividends (at least 50% of the prior year’s net income) until the capital shortfall is addressed. Since any fresh capital infusion from the national government is out of the question, the capital build up can only be achieved through earnings.

HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT, CURIOUS ACCOUNTING TREATMENTUnknown to many, the equity investments of both the LBP and DBP in Maharlika are not recorded as equity as should be done according to International Financial Reporting Standards rules. Despite the money having actually been taken out of their balance sheets by the 4th quarter of 2023, the audited FS of both LBP and DBP do not show a reduction in their CET1 and total CAR ratios. Instead, the Maharlika equity is listed as Miscellaneous Assets, as a deposit for future subscriptions to shares of stock of the Maharlika Investment Corp. (MIC). The excuse: the corporate secretary of MIC has not yet issued the stock certificates for the said investments.

This begs the question: how long does it really take for the MIC corporate secretary to issue the stock certificates for equity investments it has already received? The annual FS audited by Commission on Audit is released at least six months after the calendar year, hence there was more than enough time (nine months) to issue the said stock certificates. Officials of both the LBP and DBP say that the COA has agreed to such accounting treatment. However, COA’s consent does not necessarily make such an accounting calisthenic correct, although they would expectedly assert it is just a “timing issue.” This writer doubts if reputable external auditors would agree to such an approach.

The “delay” in the issuance of MIC shares to LBP and DBP became a convenient excuse not to reflect the reduction in CET1 and CAR ratios in the annual reports. For a high-profile investment that hogged the headlines for most of 2023, this “classification” consigns it to an accounting whisper. So much for transparency, disclosure and good governance.

(Next: The Proposed Recapitalization of LBP and DBP via IPO — An analysis of the proposed amendments to their charters)

Alexander C. Escucha is the president of the Institute for Development and Econometric Analysis, Inc., and chairman of the UP Visayas Foundation, Inc. He is a fellow of the Foundation for Economic Freedom and a past president of the Philippine Economic Society. He is an international resource director of The Asian Banker (Singapore). Send feedback to alex.escucha@gmail.com.